Tests, quizzes, writing assignments, and classroom discussions are tools that teachers use to evaluate just how neatly and deeply students have stored content knowledge in their brains. They range from multiple choice and short answer questions to word problems and essays. The former assess a student’s rote knowledge - how well he or she can recall a definition or perform arithmetic; the latter gauge children’s ability to actually use information in order to answer a question or solve a problem.

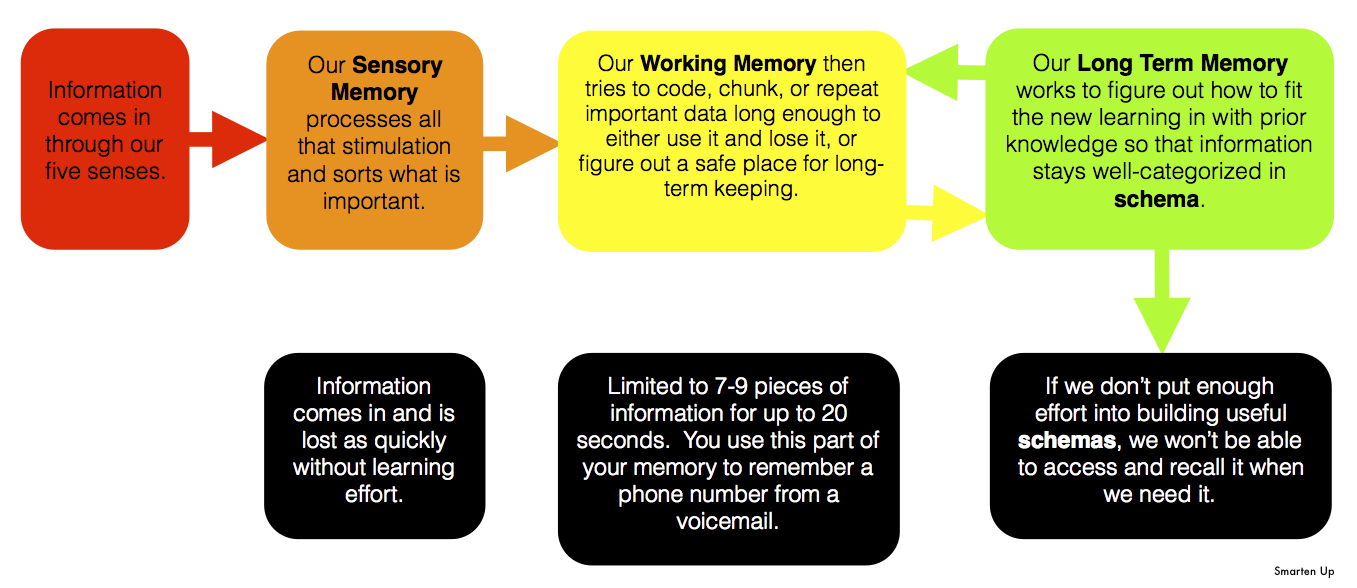

Genuine learning occurs when someone can build their understanding of a given concept from the ground up, from knowledge through evaluation; it is the difference between cramming for an assessment by memorizing a collection of vocabulary terms, and giving your mind time to learn those words in context, with the support of graphic organizers, outlines, mnemonic devices, and other memory aids. While the latter may take more time and effort in the short term, that energy will pay off when it comes time to study for a mid-term or final exam because even if you don’t remember everything, you have an efficient set of familiar, useful resources to fill in the gaps. By taking the time to build a strong, connected, sticky schema the first time around, students can avoid the chaos and anxiety that comes with last-minute academic efforts.

“But I have too much reading to do, too many assignments to finish, too many exams to study for. I just don’t have enough time.” Sound familiar? It does to me. And the truth is, students do have a lot on their plate. Balancing studies with extra curricular activities, family responsibilities, and fun is hard. Effective time management strategies will make it easier, but it will never be easy. That is what separates the diligent, neurotic A students from their peers, brainiacs aside.

So then students must ask themselves if they are ready to commit to building positive learning behaviors. Are they willing to put in the time and energy to build their executive function skills, so that they can become better students? Are they ready to more consciously identify learning goals, and then plan and follow-through with a strategy for their accomplishment? Are they prepared to think flexibly about their progress, and reflect more thoughtfully on their achievements? The choice is theirs ...