For many students, quizzes and exams are a source of anxiety and, sometimes, disappointment. But with care, planning, and sustained effort, it is possible to prepare with confidence. What is the best way to study for a test?

1. Treat every assignment and reading as a part of your preparation

The most important element of test preparation comes in the weeks (and sometimes months) before a test, as a student remains actively engaged with lectures and homework assignments, moving from knowing to understanding as they learn so that, when it comes time to study, they are already beginning from a place of confidence, rather than starting from scratch. The test is not a separate, stress-charged event in this model, but the natural culmination of weeks of learning. In concrete terms, this means that students should be taking clear notes and creating study materials as they learn the content, keeping up with readings and assignments, and independently reviewing at the end of every shorter unit.

2. Distributed Practice: spread out your studying

Studies have shown that if you believe a test will require four hours of studying in the week of the exam, it is much more effective to split up this time into smaller chunks, spread out over multiple days, than to cram all four hours on the night before the exam. So…

3. Make a study plan

It isn’t always easy for students to manage the many tasks that are thrust upon them - to use time wisely, set up a study plan well in advance of the test, with a schedule for studying that splits up the content over multiple days and a specific plan for which study strategies to employ.

4. Mix it up: use a variety of strategies

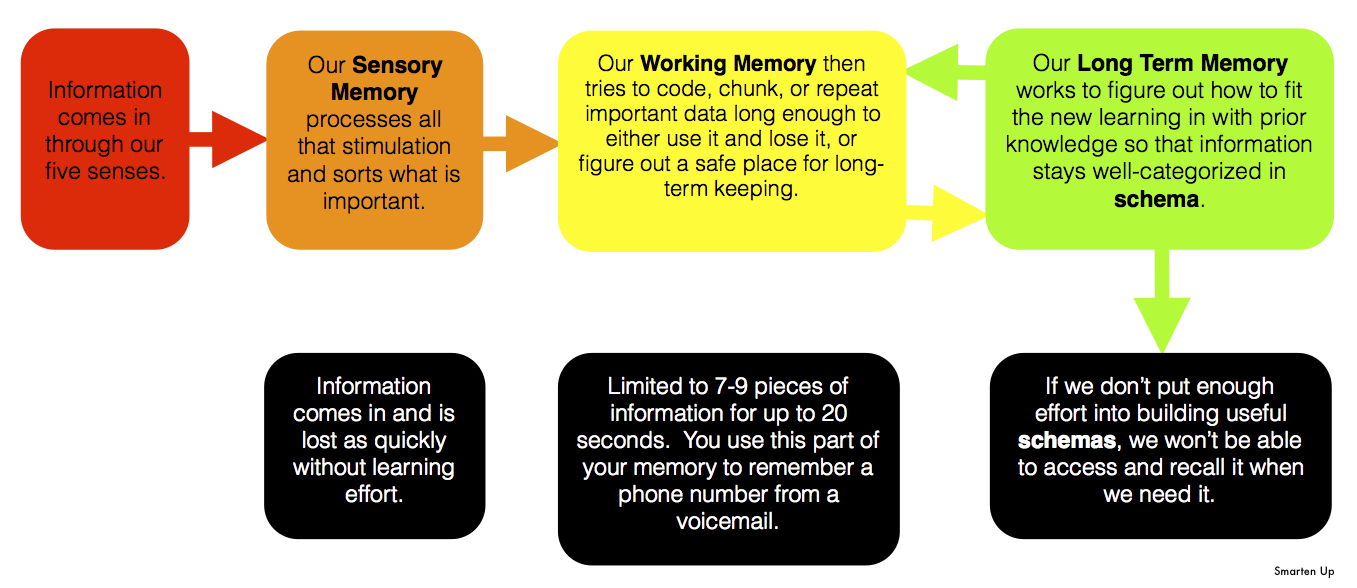

Different types of content (and different types of tests) will require different strategies - and students should also consider what strategies work best for their specific learning strengths. The more that you can approach a subject from different angles — with flashcards written in your own words, illustrated histories, timelines, online video resources, practice problems, poetic adaptations, mnemonics and memory aides, etc — the more you’ll move from knowing to understanding. Your goal should be to absorb new information with context, thinking about it as a story, rather than memorizing in isolation, by rote. Use a timer to focus for specific periods, and switch between strategies. Take active breaks, drink water, and eat healthy snacks!

5. Get a good night’s sleep

It is tempting to believe that staying up late to cram will help you conquer the test - but the truth is, giving your brain the rest it needs is more important. This is another reason why it’s important to distribute your studying across multiple days!

6. After the test, reflect!

Your job isn’t over when the test is done - take a well-deserved break, of course, but then take time to reflect on the study process and the test itself. Think about what worked, so that you can use it again next time. What areas can you identify for improvement next time?

This Smarten Up study strategies planning sheet is a great resource to create this sort of structure for students!